November 6, 2020

Redlining, Housing Policies, and More

Alicia Deluga

In October, the Sasaki Foundation hosted a virtual panel discussion entitled Redlining, Housing Policies, and More, with a panel of housing experts from the Greater Boston area and moderated by Elizabeth Christoforetti from Supernormal and the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Panelists included Amy Dain from Dain Research, Jarred Johnson from TransitMatters, Jesse Kanson-Benanav from Abundant Housing MA, and Allentza Michel from Powerful Pathways.

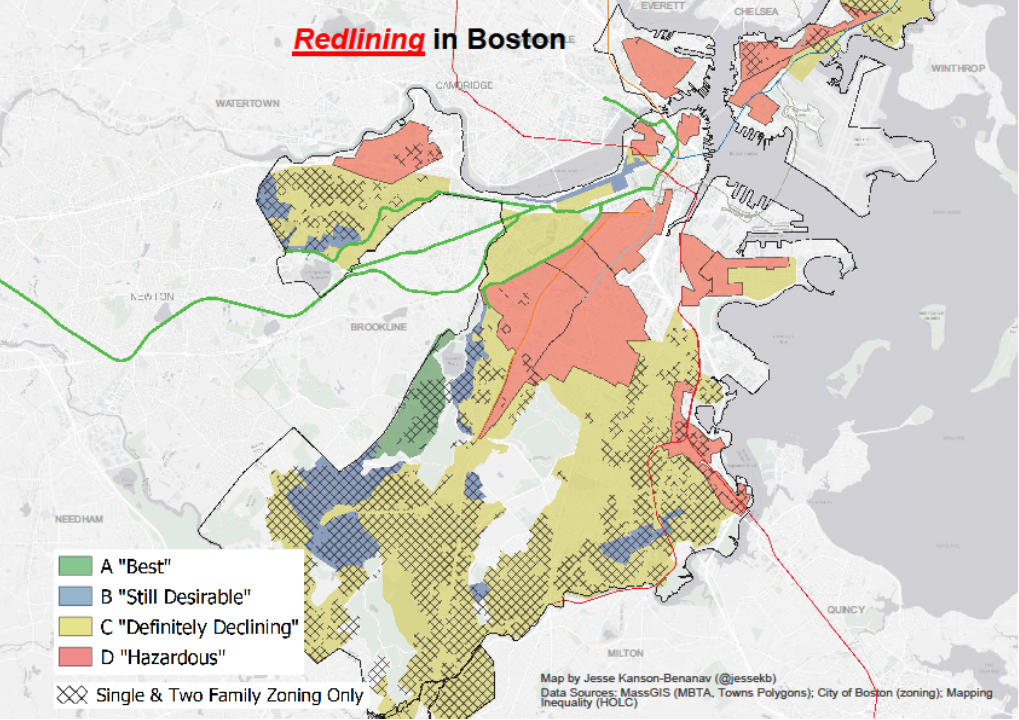

By way of background, racial discrimination in mortgage lending in the 1930s continues to shape the demographic and wealth patterns of Boston communities and communities across America. At the time, government surveyors graded neighborhoods in over 200 cities, color-coding them green for “best,” blue for “still desirable,” yellow for “definitely declining,” and red for “hazardous.” The redlined areas were ones local lenders discounted as credit risks, largely due to residents’ racial and ethnic demographics. Many communities redlined on government maps more than 80 years ago continue to struggle economically to this day. In essence, it is as though these neighborhoods, then and now largely made up of people of color, have been trapped in the past, locked into seemingly infinite poverty.

Amy Dain kicked off the discussion by describing the history of redlining throughout Greater Boston and throughout the country as a whole. In 1933, half of home mortgages were in default, and home financing was near collapse. The Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) introduced long-term (20-year) mortgages, and created maps to show banks risk areas for granting mortgages. These maps were essentially recommendations for banks: red meant do not lend, yellow meant take caution, blue meant proceed with caution, and green meant the area was safe to lend. The 1930s and 1940s were particularly tough on Boston. Amy noted that by 1950, the city was in crisis; properties were in bad decay and there was little investment. Boston lost more than 100,000 residents, which Amy mentioned was the biggest drop of any major city in the United States.

Redlining in Boston

Image courtesy Jesse Kanson-Benanav

To that end, Elizabeth asked panelists how we can lay a pathway forward for more and better affordable housing in the future. Jesse described how the process is structured for approving affordable housing and who is involved in these approvals. He noted the process was overwhelmingly developed by white homeowners who didn’t want new housing creation in their communities, and that this was apparent across the region. “When we have these conversations about the need to address the severe housing shortage, whether it’s mixed-income, market-rate, or affordable housing, we are constantly coming up against participants in these conversations who don’t represent the desire and needs of the community at large,” said Jesse.

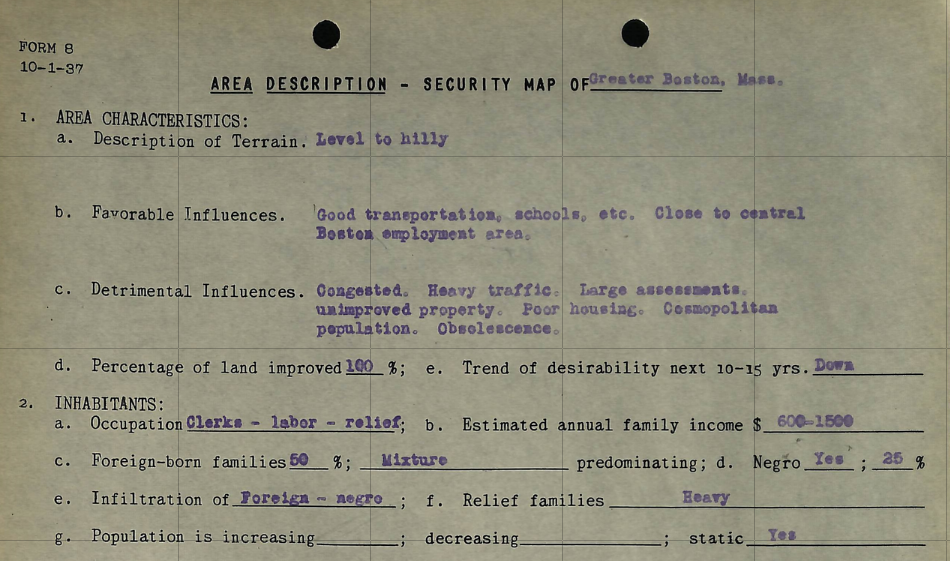

Jarred touched on the history of redlining; he mentioned that when the government finally made changes so Black and brown families could move to different places, the banks—using the government risk maps—limited Black and brown families to buying homes only in certain places. The banks went to Jewish families and used scare tactics to make them sell their homes low, then sold those homes to Black families at incredibly high rates with drive-by inspections, which resulted in record foreclosures. Jarred noted, “It’s important to make sure we understand the background and the history of exclusionary zoning practices, and that many redlined communities still suffer from a lack of transit access and a lack of investment, as well as fewer parks, which has a climate change impact that is still visible all these years later.”

portion of 1930s neighborhood lending evaluation of district in Roxbury, MA

Image via Mapping Inequality

Elizabeth asked whether there are good measures to counter displacement while still allowing for the development required to deliver supply to the market. Allentza described the many different prongs to the development story, which speaks to the existence of many different interest groups. She noted, “There are questions that need to be answered on the part of planners and policymakers in order to expand the conversation and practices to make sure that all the voices involved are actually involved.” Many examples of this exist in Cambridge and Boston; as areas are redeveloped, redevelopment includes a rebranding process that doesn’t involve the community members. She asked, “For whom are these changes being developed? Who determines and who gets to decide what communities deserve market rate versus affordability? And then, who makes the decision about what developments come in?”

Allentza is part of our Design Grants research program team the Mattapan Mapping Project, which combines nuanced demographic statistics, land use trends, and audio and video media on an online interactive platform to inform strategies by policymakers, activist scholars, and residents to confront displacement.

Elizabeth noted that the challenge, in a way, is how to marry policy and zoning with the process of identifying what concerns are arising from the neighborhood. She believes trying to find that space where these issues overlap is the best way to identify what we can actually mobilize for and respond to, ultimately achieving what’s needed by the neighborhood.

As far as development trends, Allentza described how when we look at the history of industrialization at the start of the 1900s, leading into the Great Depression, leading into the expansion of the suburbs largely due to the highway movement, we see the exodus out of cities. Now, we’re looking at a great return, she noted, and a number of external drivers, like transportation and other motivations, explain why we are seeing a lot of movement back into the cities. What we are also seeing as a result, she said, is the decentralization of wealth and affluence in the suburbs. Because people are being displaced out of cities, they’re moving to the suburbs and facing the same challenges as what they experienced while living in cities, such as lack of transportation options, limited housing options, and other forms of land-use restrictions.

Allentza noted, “We’re going through a reverse process right now, where we are seeing this influx into cities, but we are not talking enough about what’s happening to those who are being displaced out into the suburbs. It’s a reverse redlining process that we need to capture and address before the problem becomes so overloaded that we are going to have enough forms of segregated housing systems.”

Elizabeth asked a very thought-provoking question at the conclusion of the conversation: “Could there be a reason to find hope on this topic in uncertain times? What can we imagine within this unprecedented moment that might be a trigger for real and substantial change?” All panelists acknowledged that though these times are extremely uncertain, hopefully people can educate themselves on these issues that are coming to light so that we can drive change.

This topic is extremely important, and one in which we hope to continue the conversation in the future. If you have any follow up questions or thoughts, please feel free to send them to us at info@sasakifoundation.org.